|

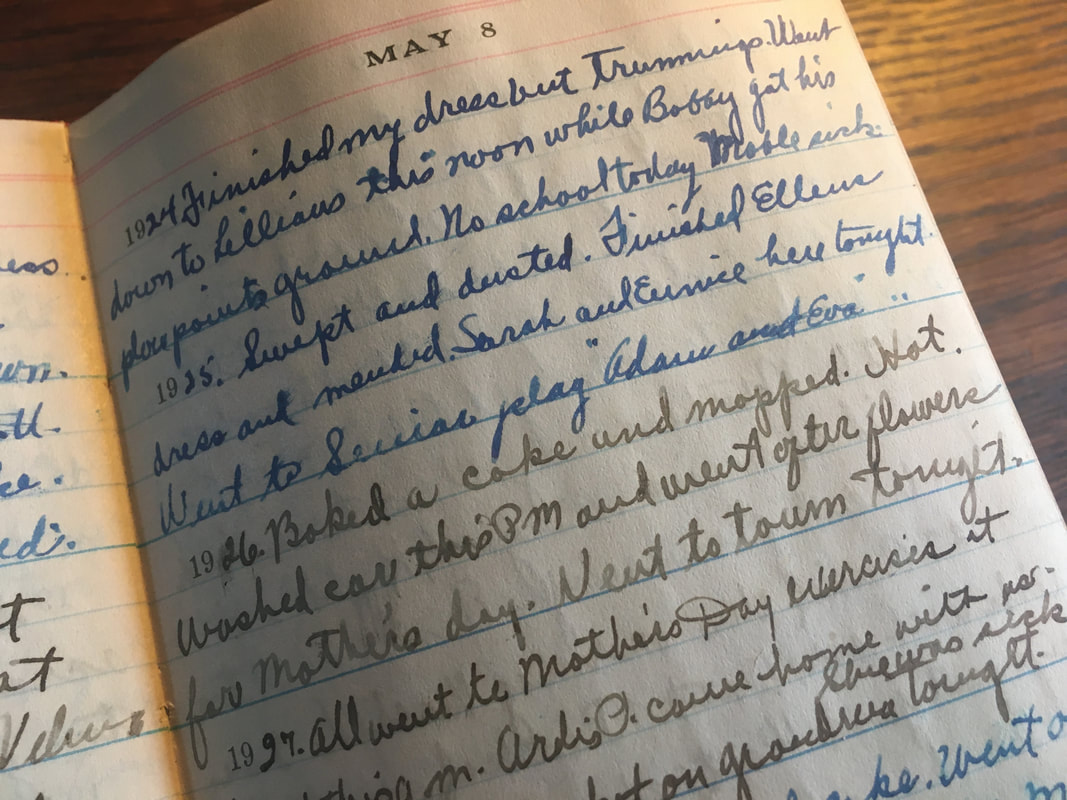

My grandmother's plain, careful script fills three lines a day in her diary starting on Jan. 1, 1924. As she sat down to make her first entry, a new year was dawning and a bitter winter storm howled outside. Her name was Fern Bruce. She was 31 years old with three children: Ellen, 8 (my mother); Robert, 7; and Don, 3. It would be another six years before her youngest was born, a daughter, Kathleen.

She lived in an old brick farmhouse with her husband Bobby just a couple miles from the farm where she grew up with 10 brothers and sisters. The diary lists births and deaths, illness and recovery, the odd and the ordinary, lots of church events, family gatherings and meetings of the WCTU, because, after all, prohibition was in force. While each entry seems ordinary enough, as a reader moves through the record of each day, life on the farm takes shape. She tells what she is reading and what she is baking, and who is visiting, all the while keeping an eye on the weather outside. Jan. 1, 1924: "The old year hated to leave us. Anyway, it went out with great bluster. Sarah and Grandpa were here for rabbit dinner." Jan. 5, 1924: "Bitter cold. Too cold to make weekly trip to town. Baked and mopped. Tonight played Flinch (a card game) with the kids." Jan. 8, 1924: "Robert did not go to school today. Butchered three hogs. Eunice and DeArle were up this evening." Jan. 17, 1924: "Canned 10 quarts of pork and rendered three gallons more of lard." Her reading on this evening was: "Never the Twain Shall Meet," a bit of a bodice ripper, apparently, by Peter B. Kyne. The synopsis of the book says: "Islander Tamea, Queen of Riva, visits and she becomes infatuated with a local man and decides to have him for her own. And she's used to getting whatever she demands." Jan. 22, 1924: "Much warmer but wind blows very hard. Ironed. Bobby bumped heads with one of the horses and hurt his eye." Feb. 13, 1924: "Baked bread and fried bars. Tied off comforter for Don's bed. Went down to see Esther's new baby this evening." March 10, 1924: "Washed and hung my clothes upstairs because there was a raging blizzard outside all day." March 25, 1924: "Ironed and mended. Eunice was up this morning for a couple chairs. Bobby cut my hair this evening." April 7, 1924: "Baked bread and washed. Hung my clothes upstairs. Snowed hard all morning. Found a lizard in the wash water. Bobby plowed for oats." At the diary's conclusion, she listed some major events of the years 1924 to 1928. May 30, 1924: Finished hatching 250 chickens. July 8, 1924: Light plant installed. (This generator brought electricity to the farm for the first time). Oct. 31, 1924: Bought a piano. Feb. 28, 1925: Bought new Reo sedan. June 14, 1926: Robert and Ellen commence piano lessons. March 28, 1927: Got a new tractor. Dec. 3, 1927: Got a new radio. Nov. 6, 1928: Hoover elected president. (Almost exactly a year later, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began.)

0 Comments

The farm in Southern Michigan where my grandparents lived was on East Horton Road between Pence Highway and Scott Highway, rural roads that cut Lenawee County into a squared off landscape of corn and bean fields. Upsetting the symmetry was Bear Creek, a scribbling meander that flowed slow and muddy beneath a two-lane bridge under East Horton Road just below the farm house. In summer, I fished for bullheads there and hugged the bridge's riveted steel rail as cars occasionally rushed by scattering dust and spitting gravel that pinged from the bridge near my feet.

My grandparents were Bobby and Fern Bruce. My grandfather was tall, slim and soft spoken. The first son in the Bruce line for four generations was a Robert, so my grandfather was known as Bobby, to distinguish him from his father, grandfather and his first son. My grandmother was short and stocky, practical and pragmatic and focused on a routine made smooth by years of repetition. After raising four children, rendering lard from butchered pigs, canning beans and fruit and cooking the meals, she was used to staying busy. The first of the Bruce clan to land in Michigan was my great, great grandfather Robert. He was born in Ireland about 1829 and was just coming of age when blight killed the potato crop and he joined millions of others and fled to America. On Aug. 11, 1849, he sailed from Liverpool, England. On the passenger list, he said his occupation was "immigrant." He was 20 years old. Southern Michigan was a popular spot for the Irish. Many landed in Detroit to work in factories. Others made their way further west to the rural areas where soils were rich and farms were available. The northwest corner of Lenawee County is an area known as the Irish Hills, named for the many Irish immigrants who called that place home. By 1860, 11 years after he left Ireland, he owned a farm, had a wife, Margaret, also born in Ireland, and three children. In 1863, he was drafted into the Union Army to fight in the Civil War. By 1870, he was back on the farm, presumably, the one I came to know, and he had five children. Both he and Margaret indicated on census forms they could not read or write. Death came to Margaret first on Oct. 6, 1897. Heart failure. Robert followed a few months later on June 7, 1898, and the farm passed to Robert's first son, my great grandfather and eventually to my grandfather. I loved that farm. Each spring, two small lily ponds under shade trees in the back yard were full of black dot frog's eggs suspended in jelly. Quickly they became tadpoles who grew tiny feet and by summer they stared back at me as leopard frogs. Wild cats patrolled the barn for mice, and in summer we picked beans, peas, melons and corn from a large garden next to the driveway. A chicken coop stood on one side of the barnyard, and sometimes I was sent there to gather eggs. Looming large at the end of the farm yard was a big red barn where steers milled in tight quarters. Bales of hay were piled like blocks in the hayloft, and from a square hole in the floor above the cattle pens I watched my grandfather push through the steers below, occasionally swatting them with a coiled rope he held in one hand to move them out of the way. A garage stood next to the house, and tacked above its door was an embossed metal sign indicating this was a centennial farm, one held in the same family for at least 100 years. I was impressed. I still am. More than 100 years beyond Ireland. Beyond hunger and illiteracy. More than 100 years beyond an ocean crossing, beyond Civil War battles and the birth of five children. And there, improbably, I stood, 10 years old, five generations beyond arrival, on ground where a new promise was realized, at the edge of a cornfield on a hill above Bear Creek. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed