|

A string of red, plastic bells stretched across the front of the house, and a wreath of cedar, fir and holly hung on the door. It was almost Christmas and inside a potluck for the dinner bridge group was arranged on a counter in casserole dishes and on platters.

The mood was boisterous. My father was a theater professor, and his colleagues reveled in a story well told. Bridge gatherings and other social events tended to be loud, with lots of laughter and broad gestures for emphasis. Five card tables were set up in what my mother called "the keeping room," and shuffling cards and clinking glasses and spoons filled the air as cards were dealt, bids were made and scores were kept. Bridge is different from most card games; when your partner wins the bid, you lay your cards face up on the table and your partner plays your hand. You are, as they say, the dummy. Near the midpoint of the evening, my father's partner prevailed in the bidding, and he laid down his cards by suit, hearts and clubs, diamonds and spades. He wished his partner luck, excused himself from the table, went to the bathroom and behind a closed door collapsed from a massive heart attack. He was technically alive when a guest discovered him a few minutes later, but only technically. He never regained consciousness. In the days that followed, family members arrived from the far-flung corners of the country, and we tended to flower deliveries, accepted gifts of home-cooked meals and gratefully welcomed friends and relatives. At some point my mother gathered a few things that were my father’s and asked if people were interested in them. I’m not sure why, but when she asked if anyone wanted my father’s stamp collection, I said, “I’ll take it.” Maybe in my grief I was just being protective of things that reflected his life, or maybe it was because no one else seemed to care, and I thought someone should. I’m not sure. Whatever motivated me, weeks later I found myself back at home opening the cardboard box. Inside was a handsome album full of stamps, hinged and labeled. There was a flimsy wooden box with a sliding lid that contained some loose stamps, a bundle of early letters rescued from my Aunt Pearl’s belongings that dated to the late 1850s (with stamps), some postcards (stamped) and a collection of first-day covers -- envelopes carrying fancy cancellations from the first day a stamp was issued. Tucked in among the envelopes, I found a small, brown notebook. In a cursive hand, it was titled: “Interesting & Useful Things About Stamps” It was dated 1930 and copyrighted, obviously a draft of a planned book. My father, Harold Obee, was the author, and by the 1930 date, was 15 years old when he created it. That brought a chuckle. I can’t ever remember a time when my father wasn’t professorial, some now would say “nerdy,” and here was documentary evidence to prove that was true long before I was born. The book was carefully outlined with Roman numerals. Chapter I would be the history of stamps, and the following chapters would deal with how to start a collection, how stamps are sold, how to correctly mount them, and on and on. At the top of one page, he offered instructions on what to do if the text came up short. “Jokes to fill up rest of page at the end of chapters.” I always knew my father was a stamp collector. He bought me my own stamp album when I was quite young, and I can remember him towering over me as I soaked pieces of envelopes in water to remove their stamps. I remember he would occasionally dole out stamps to me that were duplicates from his own collection, but I never suspected this hobby was more than an idle pursuit for him. The loose notes I found with his stamp album, the unfinished book and the care with which he assembled his collection in the late 20s and early 1930s made me realize this hobby was among the first things in this world to thoroughly engage him, and he probably had many fond memories of his early collecting. It was 1930 after all, in the heart of the Depression, and the world around him wasn’t offering a lot of promise. Knowing all of that, it’s easy to picture him at his own small desk in his own world as he spread the stamp collector’s tools of measurement and close inspection in front of him and immersed himself in the swirls of fine engravings and subtle color variations. It’s easy to picture because all my life I had seen my father in just that pose, surrounded by his books with a desk lamp pulled low, making careful notations on a manuscript in front of him. So this is where all of that started? This was where he first honed his scholarly approach? Stamps? From the collection, it’s clear he was only seriously active as a collector in the early to mid 1930s. By far, most of the loose stamps are from that time. But among the items in the box with the album were first day covers from as late as the mid 1980s, proof that his interest continued. And I know he put albums in the hands of every one of his children, I’m sure in the hope that they might also learn as he learned and fall into that world he had known and loved when he was a teenager. Suddenly, I knew why I had his stamp collection. I had to put it in order. I’ve never really been fascinated by stamps, and I knew almost nothing about them. You often hear about rare and very valuable stamps, so of course that was my first thought as I waded in, but you learn pretty quickly that for most stamp collectors, an example worth $50 is a major find and most of the values for frequently encountered stamps seldom top a few bucks. Before too long my focus changed from value to the beauty of the fine engravings on those early stamps and the history they document. National parks canonized. Major historical events remembered. Famous presidents honored. Early airmail stamps featuring zeppelins are very popular. Fortunately, it was easy to get oriented. My focus was basically the first 100 years of stamps in the United States, because that’s what I had in front of me. That’s the first lesson of stamp collecting. Limit yourself to an era, or a country, or a type of stamp. I began. The first official stamp was issued by the federal government in the United States on July 1, 1847. To review which stamps were issued after that, one need only consult the Scott stamp catalog. J.W. Scott, a stamp dealer in New York, published his first stamp catalog in 1868, assigning numbers to each postage stamp and drawing distinctions between them. This was necessary because some stamps to the naked eye look quite similar, but on close inspection are from a different engraving or are of a different color. The first Scott catalog quickly became the key reference work for collectors, and today the Scott numbering system is the main framework for collectors in the United States. The original catalog was a 21-page pamphlet. Today the Scott catalog has more than 5,000 pages. Not only does it number, identify and price stamps from the United States, it lists virtually all stamps used for postage from around the world. The catalog has had such an impact that today many stamps are more recognizable as a Scott number than from their physical description. The first thing I noticed about my father’s stamp collection was that the Scott numbers did not always line up. At first I thought this was because my father made mistakes in his identification, but then I realized the numbering system was altered over the years, with numbers added and certain stamps winning the right to have their own Scott number. So that was the first chore; checking to see if my father’s initial identification was correct and had stood the test of time. I also remembered hearing that my father had some rare confederate stamps, so I turned to that section of the album. There were only two. One appeared to be a Scott CSA #6 or #7, but the color was wrong. I trolled the Internet and found a very helpful site on confederate stamps and emailed my questions: “I have an unused CSA #6 or #7, not sure which. The color is what has me baffled. It is clearly a light green. I suppose you could say it is a blue green, but it is definitely different than the examples on your site. Is there a history of color differences with this stamp, or are we just dealing with a blue stamp whose color has changed over the years?” Almost immediately, I got the following answer: “The blue-green color of a CSA #6 stamp is probably the New York Counterfeit. You can read about the New York Counterfeit and see an example in the fake stamps section on my website,” responded John L. Kimbrough at, where else, www.csastamps.com. “I hate to tell you this Dad, but your rare confederate stamp is a fake,” I said to myself. I could almost hear him talk back. “Well, I’ll be darned,” he would have said. For an aspiring stamp collector, it doesn’t take long to know and identify the main groupings of important U.S. stamps issued from 1847 to 1947. They are clearly identified in the Scott catalog, or in any book on stamp collecting. One series popular with collectors is the first commemorative stamp set. Called the Columbian Issue, it is 16 stamps that mark the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. They are quite beautiful and range from a 1 cent to a $5 stamp. The stamps with values of a dollar or more in good condition can bring prices ranging from $1,500 to $10,000. The higher the face value, generally, the fewer that were printed and the rarer they are today. Of course, a full set of Columbians would be a necessary part of any serious American collection. My father’s collection contained seven, all the more common 10 cent and under face values. As is the case with antiques or other collectibles, the goal is to find stamps in unused, mint condition, finely printed and well centered on the paper, and the best stamps still have all the original gum on the back. While using stamp hinges to mount stamps is popular, for a mint condition stamp it is better to keep them unhinged and mounted in plastic sleeves. Of course, it is sometimes difficult to find mint examples of the early stamps, or, if you can find them, they are expensive. To fill in your collection, you can settle for ones that are used for a fraction of the price. I suppose, at may age, I should quit being surprised that my father is still teaching me, even all these years after his death in 1989. I also shouldn’t be surprised I am still learning about him. Inside the pages of that stamp album and related ephemera his young voice speaks with a cadence and inflection that is warm and familiar. I haven’t become an ardent collector, or anything approaching that, but every so often, on rainy winter days, I pull out the album to spend some time with it, and it feels like a chance to talk to my father again. He is there in those loose sheaves of paper, in the careful script of his handwritten notes and in the hobby that gave him pleasure. And every time I learn something surprising about a stamp, or correct an error in the album, I feel like I am sharing that discovery with him again, just as I did some 65 years ago, when I was just becoming aware and his hand was guiding mine.

0 Comments

They say because my next oldest brother is seven years older, and my younger brother is seven years younger, I am, psychologically speaking, an only child. I don’t know if this is true, but if it is, it might be the reason I sought companionship in the pages of books when I was very young.

We lived in an older Cape Cod style home where the upstairs ceiling sloped to low walls, leaving full headroom only in the middle of the room. That was where I slept for most of my early years, and I vividly remember sitting cross legged on my single bed with books scattered around me. I was, what? Four? One of the first books to captivate me was Cowboy Small, written by Lois Lenski in 1942. It was printed mainly in black and white with one orange color used throughout for highlights. Cowboy Small’s horse was Cactus (orange and white), and Cowboy Small’s kerchief was orange, as were his chaps. When he climbed into his bed, he snuggled under an orange blanket, and out on the range at night, he gathered with other cowboys around the orange flames of a campfire and played an orange guitar. I loved everything about that book: heading out on a horse and camping on the range, building a small fire and rolling out my bedroll. I could almost taste the smoky air. But the thing that really intrigued me were all the things he needed to a cowboy, all of which were neatly detailed at the back of the book. In addition to his regular clothes, he had to have a hat, a gun belt and holster, a kerchief, a cowboy shirt, chaps, blue jeans, spurs and boots. Equipment consisted of a plate and silverware, coffee pot, a can of beans, a horseshoe, lariat, a branding iron and a bedroll. Cactus needed a bridle and reins, a saddle with stirrups and a pommel and a saddle blanket. Pointing to each item, I repeatedly went through the list, memorizing each item. I knew I would need to know these things if I was a cowboy someday. The other day as I was getting ready for a short camping trip, I was laying out the things that I needed to take with me. A knife, my backpack, sleeping bag, tent, backpacking stove and propane, flashlight, sleeping pad, water bottle, first aid kit, compass, and my fishing gear – two rods, four reels, sinking and floating line, and assorted dry flies, nymphs and streamers -- and I flashed on Cowboy Small. The list of gear. Everything you needed. Carefully and thoughtfully assembled. It occurred to me that this is a process I've used all my life and that while Cowboy Small was just a children’s book, it cleared a mental trail I have always followed, a path now wide and well worn by practice and experience. Sadly, I never got to be a cowboy, but when words were first decipherable and when ideas were just taking shape, I was learning how to be ready. I slammed the tailgate on my truck and took one last look at my gear and provisions. All was in order. I was ready to ride. Mary spied the nest first, clinging to a spindly branch on a decades-old lilac bush at the end of our driveway. It was tiny, and woven with spider silk, plant downs, feathers and moss -- a hummingbird’s nest for sure.

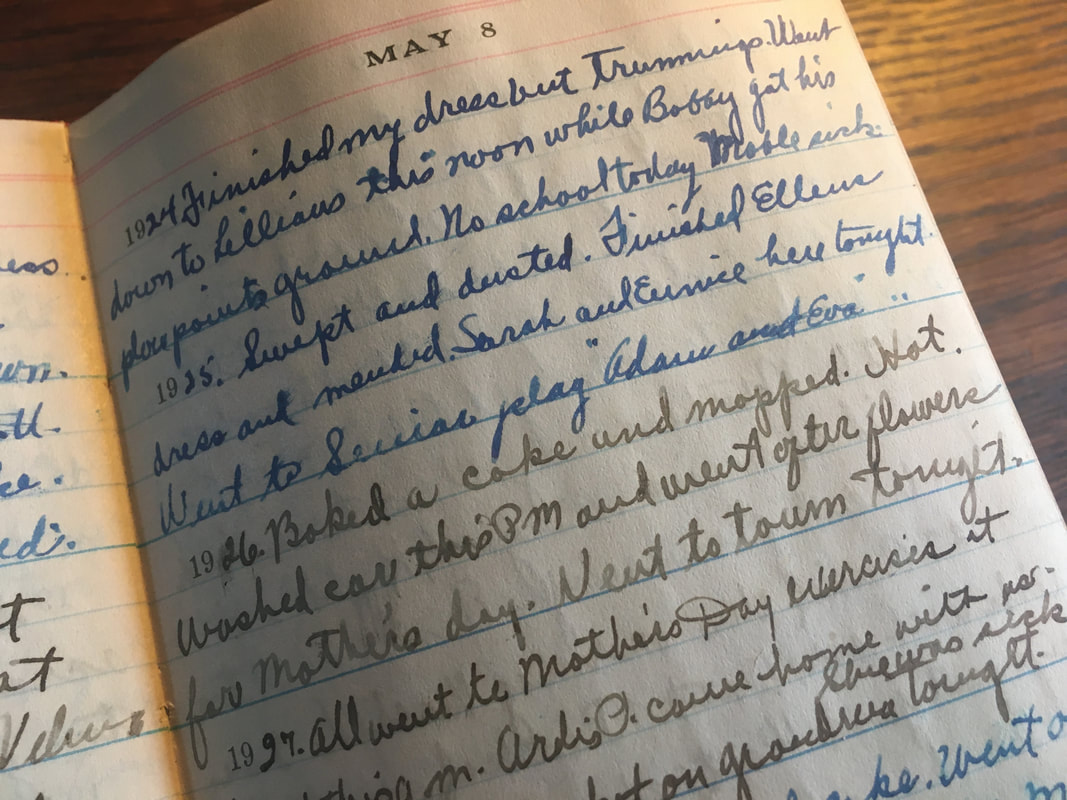

Gently pulling it to eye level, we looked inside. Empty. We didn’t know whether it was used and abandoned or in the process of becoming, so we left it alone, cradled there in a fork of a twisted branch. On a return from a day trip, Mary checked the nest again. This time, we saw the unmistakable silhouette of a hummingbird, her tiny body nestled on the cup-like nest. She remained still as we approached. We’ve encouraged hummingbirds to visit our home with plantings they love. Fucia, penstemon, cat mint and phlomis to name a few. And I’ve seen them sipping nectar from our apple blossoms as well, but this was the first time we saw one nesting. I think she is an Anna's hummingbird, the kind who stays nearby all year. Her tiny nest probably will hold two white eggs about the size of a coffee bean. She will incubate them for 15 to 18 days until the hatchlings emerge with eyes closed, tiny and featherless and dark in color with small yellow beaks. If all goes well, they will fledge three or four weeks after hatching and take their first flight. We’ll watch anxiously until then. On its slender lilac perch, the nest bounces perilously in even gentle winds. The whims of nature sometimes can be a heartless thing, we know, especially for young birds who perch in precarious places. My grandmother's plain, careful script fills three lines a day in her diary starting on Jan. 1, 1924. As she sat down to make her first entry, a new year was dawning and a bitter winter storm howled outside. Her name was Fern Bruce. She was 31 years old with three children: Ellen, 8 (my mother); Robert, 7; and Don, 3. It would be another six years before her youngest was born, a daughter, Kathleen.

She lived in an old brick farmhouse with her husband Bobby just a couple miles from the farm where she grew up with 10 brothers and sisters. The diary lists births and deaths, illness and recovery, the odd and the ordinary, lots of church events, family gatherings and meetings of the WCTU, because, after all, prohibition was in force. While each entry seems ordinary enough, as a reader moves through the record of each day, life on the farm takes shape. She tells what she is reading and what she is baking, and who is visiting, all the while keeping an eye on the weather outside. Jan. 1, 1924: "The old year hated to leave us. Anyway, it went out with great bluster. Sarah and Grandpa were here for rabbit dinner." Jan. 5, 1924: "Bitter cold. Too cold to make weekly trip to town. Baked and mopped. Tonight played Flinch (a card game) with the kids." Jan. 8, 1924: "Robert did not go to school today. Butchered three hogs. Eunice and DeArle were up this evening." Jan. 17, 1924: "Canned 10 quarts of pork and rendered three gallons more of lard." Her reading on this evening was: "Never the Twain Shall Meet," a bit of a bodice ripper, apparently, by Peter B. Kyne. The synopsis of the book says: "Islander Tamea, Queen of Riva, visits and she becomes infatuated with a local man and decides to have him for her own. And she's used to getting whatever she demands." Jan. 22, 1924: "Much warmer but wind blows very hard. Ironed. Bobby bumped heads with one of the horses and hurt his eye." Feb. 13, 1924: "Baked bread and fried bars. Tied off comforter for Don's bed. Went down to see Esther's new baby this evening." March 10, 1924: "Washed and hung my clothes upstairs because there was a raging blizzard outside all day." March 25, 1924: "Ironed and mended. Eunice was up this morning for a couple chairs. Bobby cut my hair this evening." April 7, 1924: "Baked bread and washed. Hung my clothes upstairs. Snowed hard all morning. Found a lizard in the wash water. Bobby plowed for oats." At the diary's conclusion, she listed some major events of the years 1924 to 1928. May 30, 1924: Finished hatching 250 chickens. July 8, 1924: Light plant installed. (This generator brought electricity to the farm for the first time). Oct. 31, 1924: Bought a piano. Feb. 28, 1925: Bought new Reo sedan. June 14, 1926: Robert and Ellen commence piano lessons. March 28, 1927: Got a new tractor. Dec. 3, 1927: Got a new radio. Nov. 6, 1928: Hoover elected president. (Almost exactly a year later, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began.) The farm in Southern Michigan where my grandparents lived was on East Horton Road between Pence Highway and Scott Highway, rural roads that cut Lenawee County into a squared off landscape of corn and bean fields. Upsetting the symmetry was Bear Creek, a scribbling meander that flowed slow and muddy beneath a two-lane bridge under East Horton Road just below the farm house. In summer, I fished for bullheads there and hugged the bridge's riveted steel rail as cars occasionally rushed by scattering dust and spitting gravel that pinged from the bridge near my feet.

My grandparents were Bobby and Fern Bruce. My grandfather was tall, slim and soft spoken. The first son in the Bruce line for four generations was a Robert, so my grandfather was known as Bobby, to distinguish him from his father, grandfather and his first son. My grandmother was short and stocky, practical and pragmatic and focused on a routine made smooth by years of repetition. After raising four children, rendering lard from butchered pigs, canning beans and fruit and cooking the meals, she was used to staying busy. The first of the Bruce clan to land in Michigan was my great, great grandfather Robert. He was born in Ireland about 1829 and was just coming of age when blight killed the potato crop and he joined millions of others and fled to America. On Aug. 11, 1849, he sailed from Liverpool, England. On the passenger list, he said his occupation was "immigrant." He was 20 years old. Southern Michigan was a popular spot for the Irish. Many landed in Detroit to work in factories. Others made their way further west to the rural areas where soils were rich and farms were available. The northwest corner of Lenawee County is an area known as the Irish Hills, named for the many Irish immigrants who called that place home. By 1860, 11 years after he left Ireland, he owned a farm, had a wife, Margaret, also born in Ireland, and three children. In 1863, he was drafted into the Union Army to fight in the Civil War. By 1870, he was back on the farm, presumably, the one I came to know, and he had five children. Both he and Margaret indicated on census forms they could not read or write. Death came to Margaret first on Oct. 6, 1897. Heart failure. Robert followed a few months later on June 7, 1898, and the farm passed to Robert's first son, my great grandfather and eventually to my grandfather. I loved that farm. Each spring, two small lily ponds under shade trees in the back yard were full of black dot frog's eggs suspended in jelly. Quickly they became tadpoles who grew tiny feet and by summer they stared back at me as leopard frogs. Wild cats patrolled the barn for mice, and in summer we picked beans, peas, melons and corn from a large garden next to the driveway. A chicken coop stood on one side of the barnyard, and sometimes I was sent there to gather eggs. Looming large at the end of the farm yard was a big red barn where steers milled in tight quarters. Bales of hay were piled like blocks in the hayloft, and from a square hole in the floor above the cattle pens I watched my grandfather push through the steers below, occasionally swatting them with a coiled rope he held in one hand to move them out of the way. A garage stood next to the house, and tacked above its door was an embossed metal sign indicating this was a centennial farm, one held in the same family for at least 100 years. I was impressed. I still am. More than 100 years beyond Ireland. Beyond hunger and illiteracy. More than 100 years beyond an ocean crossing, beyond Civil War battles and the birth of five children. And there, improbably, I stood, 10 years old, five generations beyond arrival, on ground where a new promise was realized, at the edge of a cornfield on a hill above Bear Creek. |

Archives

April 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed